21 DETERMINING THE SEVERITY OF NEUROLOGICAL INVOLVEMENT

TYPES OF INCOMPLETE CORD INJURY:

A number of cord syndromes are recognised. These include the following.

THE COMMON LESIONS

22 Injuries to the cervical spine: Diagnosis: Suspect involvement of the cervical spine where the patient: 1. Complains of neck, occipital or shoulder pain after trauma; 2. Has a torticollis (Illus.), complains of restriction of neck movements or supports the head with the hands, or 3. Is found unconscious after a head injury, especially in road traffic accidents. In all cases, further investigation by radiographs is essential.

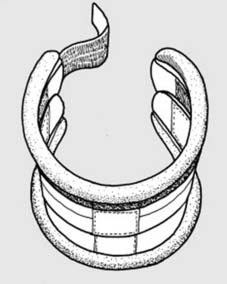

23 Initial management (a): If you suspect that the cervical spine has been injured, your first move should be to safeguard the cord by controlling neck movements. The simplest and best way of doing this is by applying a cervical collar. (Illus.: commercially available collar adjustable in depth and girth.) At the roadside, an adequate collar may be fashioned from rolled newspapers pushed into a nylon stocking and wrapped round the neck.

24 Initial management (b): Alternatively, if the patient is on a trolley, the head may be supported by sandbags. Do not allow the head to flex forwards, and do not hyperextend. Keep the head in a neutral position wherever possible, and in the conscious patient quickly check that there is active movement in all limbs.

25 Initial management (c): Especially if there is some evidence of neurological involvement, do not check the range of movements in the cervical spine. Accompany the patient to the X-ray department, supporting the head during the positioning of the tube and making sure that the spine is not forced in to flexion. For initial screening an AP, lateral and a through-the-mouth projection of C1 and C2 should be taken.

26 Initial management (d): If these films appear normal, you may proceed in reasonable safety to 1. Further examination of the neck for localising tenderness, restriction of active movements and protective spasm, and 2. A more thorough neurological examination. If these show no departure from normal, the patient may be treated with a cervical collar, with a follow-up review in 1 week.

27. Initial management (e): Investigate further if there is persistent limitation of movements or evidence of neurological disturbance. CT and MRI scans are likely to provide the best additional information. CT scans may help show hard-to-see fractures, especially of the neural arches and facet joints, and define any neural canal encroachment in burst fractures.

MRI scans may be able to show the state of the posterior ligament complex and the intervertebral discs. Alternatively, the following additional radiographs should be taken: 1. Two more lateral projections, one in flexion and one in extension; these again should be supervised; 2. Right and left oblique projections of the cervical spine.

The commonest difficulty is the technical one of visualising the lower cervical vertebrae in the stocky patient. The upper border of T1 must be seen. Accept that detail may be poor. Do not accept that the spine cannot be shown in sufficient detail to exclude dislocation of one vertebra over another. If necessary, assist the radiographer by arranging for traction to be applied to the arms – one in adduction and the other in abduction; slight angulation of the tube and increase in exposure may be helpful. In some cases screening of the cervical spine movements may be useful.

28 Classification of cervical spine injuries: Injuries of the cervical spine may be grouped according to the mechanism of injury:

(Note that injuries involving the proximal cervical spine are dealt with separately at the end of the following section.)

29 Causes of flexion and flexion/rotation injuries: These may result from: 1. Falls on the back of the head leading to flexion of the neck, e.g. in motor cycle spills, diving in shallow water, pole vaulting and rugby football. 2. Blows on the back of the head from falling objects (e.g. in the building and mining industries). 3. Rapid deceleration in head-on car accidents.

30 Flexion injuries: Stable anterior wedge (compression) fracture (a): The vertebral body is wedged anteriorly, while the posterior part is generally intact. Instability must be excluded: there must be no evidence of injury to the posterior ligament complex, with no separation of the vertebral spines (which the radiograph here suggests may possibly be present). Check if possible with an MRI scan. Eliminate damage to the neural arches or facets. Flexion and extension laterals may be carried out to exclude instability.

31 Stable anterior wedge fracture (b): Assuming these criteria are satisfied, neurological disturbance is rare and the prognosis excellent. Treat with a cervical collar for 6 weeks. Rarely when there is a degree of lateral wedging there may be troublesome nerve root involvement usually with (mainly) sensory disturbance in the corresponding dermatome. If instability is at all suspected, treat as a cervical dislocation.

32 Flexion/rotation injuries: Unilateral dislocation with a locked facet joint (a): One facet joint dislocates, so that in the lateral projection of the cervical spine one vertebral body is seen to overlap the one below (i.e. there is anterior translation of the upper vertebra with regard to the vertebra below) by about a third. The AP view may not be helpful, or it may show malalignment of spinous processes. There is often little difference between laterals taken in flexion and extension.

33 Unilateral dislocation (b): Oblique projections will, however, confirm the diagnosis. On one side the columnar arrangement of bodies, foramina and facet joints will be regular (Illus.), while on the other (see next frame) it will be broken. Damage to the posterior ligament complex is variable, and after reduction these injuries may be quite stable – but note: if there is an associated fracture involving a facet joint the injury is most certainly unstable and after reduction, fusion will be required.

34 Unilateral dislocation (c): The oblique radiograph shows a dislocated facet joint. In all cases requiring reduction a pre-operative MRI scan should be carried out to exclude a disc rupture: a significant prolapse may merit an anterior discectomy and interbody fusion in case manipulation precipitates a further disc protrusion and a catastrophic neurological problem. In the elderly especially, manipulative reduction also carries a risk of causing a central cord syndrome, so that an open procedure may then be preferred.

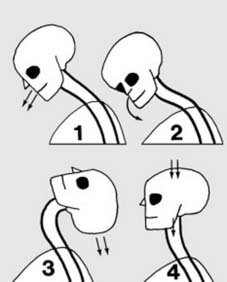

35 Unilateral dislocation (d): On clinical examination of the patient with a unilateral dislocation, the head is slightly rotated and inclined to the side (1) away from the locked facet (2). There is often great pain with radiation (3) due to pressure on the nerve root at the level of the affected joint, and (rarely) there may be cord involvement. Proceed to treatment if there is no neurological defect or significant disc prolapse: otherwise see Frame 25.

36 Treatment (a): The initial aim in treatment is to reduce the dislocation, and the secret of this is well-controlled traction. 1. The patient is given a general anaesthetic; the head must be well supported during induction, the administration of any muscle relaxant and intubation (which must be carried out without undue extension of the neck). 2. X-ray facilities should be available (preferably an image intensifier).

37 Treatment (b): 3.The surgeon must have freedom to manipulate the head, and may do this with the patient fully on the table, or pulled up till the head is supported in the lap of the surgeon seated at the top end of the table. Place the thumbs under the jaw, clasp the fingers behind the occiput, and apply firm traction in lateral flexion away from the side of the locked facet, i.e. in the direction the head is usually inclined.

38 Treatment (c): 4. Maintaining traction, bring the head into the midline position, correcting the rotation element before lateral flexion. Release the traction, support the head (e.g. with foam plastic blocks) and confirm reduction with the image intensifier or by check radiographs. If, however, reduction has not been achieved, repeat the manoeuvre with greater anaesthetic relaxation. If reduction fails (rare), or if preferred, apply traction using skull tongs or a halo as for a bilateral facet dislocation.