The diagnosis of fractures and principles of treatment

How to diagnose a fracture 25

Treatment of fractures 31

How to diagnose a fracture

1 History

In taking the history of a patient who may have a fracture, the following points may prove to be helpful, especially when there has been a traumatic incident.

Diagnosis

In some cases the diagnosis of fracture is unmistakable, e.g. when there is gross deformity of the central portion of a long bone or when the fracture is visible as in certain compound injuries. In the majority of other cases, a fracture is suspected from the history and clinical examination, and confirmed by radiography of the region.

2 Inspection (a) Begin by inspecting the limb most carefully, comparing one side with the other. Look for any asymmetry of contour, suggesting an underlying fracture which has displaced or angled.

3 Inspection (b) Look for any persisting asymmetry of posture of the limb, for example, persisting external rotation of the leg is a common feature in disimpacted fractures of the femoral neck.

4 Inspection (c) Look for local bruising of the skin suggesting a point of impact which may direct your attention locally or to a more distant level. For example, bruising over the knee from dashboard impact should direct your attention to the underlying patella, and also to the femoral shaft and hip.

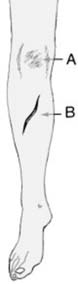

5 Inspection (d) Look for other tell-tale skin damage. For example (A) grazing, with or without ingraining of dirt in the wound, or friction burns, suggests an impact followed by rubbing of the skin against a resistant surface. (B) Lacerations suggest impact against a hard edge, tearing by a bone end, or splitting by compression against a hard surface.

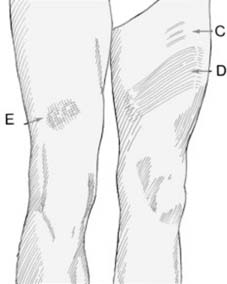

6 Inspection (e) Note the presence of: (C) skin stretch marks, (D) band patterning of the skin, suggestive of both stretching and compression of the skin in a run-over injury, (E) pattern bruising, caused by severe compression which leads the skin to be imprinted with the weave marks of overlying clothing. Any of these abnormalities should lead you to suspect the integrity of the underlying bone.

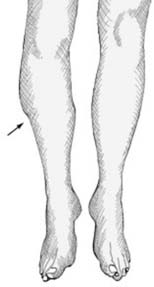

7 Inspection (f) If the patient is seen shortly after the incident, note any localised swelling of the limb (1). Later, swelling tends to become more diffuse. Note the presence of any haematoma (2). A fracture may strip the skin from its local attachments (degloving injury); the skin comes to float on an underlying collection of blood which is continuous with the fracture haematoma.

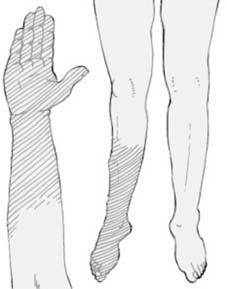

8 Inspection (g) Note the colour of the injured limb, and compare it with the other. Slight cyanosis is suggestive of poor peripheral circulation; more marked cyanosis, venous obstruction; and whiteness, disturbance of the arterial supply. Feel the limb, and note the temperature at different levels, again comparing the sides. Check the pulses, and the rapidity of pinking-up after tissue compression.