The shoulder girdle and humerus Fractures of the clavicle

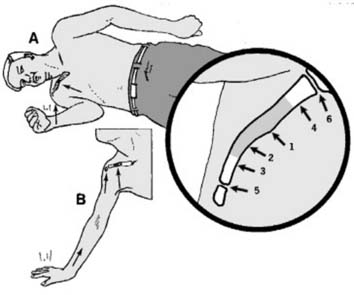

1 Clavicular injuries: mechanism of injury: Most (94%) clavicular injuries result from a direct blow on the point of the shoulder, generally from a fall on the side (A). Less commonly, force may be transmitted up the arm from a fall on the outstretched hand (B). Under the age of 30 years, road traffic and sporting injuries are the commonest causes.

Fracture: The central 3/5 (1) is involved in about 2/3 of cases, and within this group fractures at the junction of the middle and outer thirds (2) are commonest. Fractures of the outer 1/5 (3) are much less common, and of the inner 1/5 (4) even less so. Subluxations and dislocations: These may involve the acromioclavicular joint (5) or the sternoclavicular joint (6). Fractures of the clavicle involving the acromioclavicular joint are uncommon (2.8% of cases).

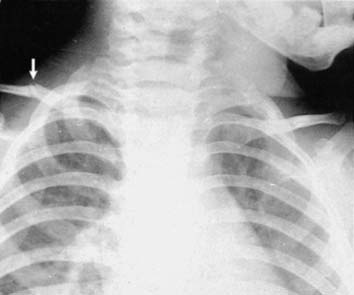

2 Common patterns of fracture (a): Greenstick fractures are common, particularly at the junction between the middle and outer thirds. Fractures may not be particularly obvious on the radiographs and it is often helpful in children to have both shoulders included for comparison. The only abnormality visible in many cases is local kinking of the clavicular contours. Healing of this type of fracture is rapid, and reduction is not required.

3 Common patterns of fracture (b): In the adult, undisplaced fractures are also common, and are comparatively stable injuries. Late slipping is rare. Symptoms settle rapidly and minimal treatment is required.

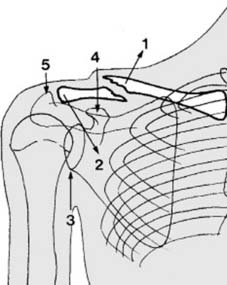

4 Common patterns of fracture (c): With greater violence, there is separation of the bone ends. The proximal end under the pull of sternomastoid often becomes elevated (1). The shoulder loses the prop-like effect of the clavicle, so that it tends to sag downwards and forwards (2). Note (3) the glenoid, (4) the coracoid, (5) the acromion.

5 Common patterns of fracture (d): With greater displacement there is overlapping and shortening, but union is usually rapid. Remodelling, even in the adults, is so effective that strenuous attempts at reduction are unnecessary. Rare non-union is nevertheless seen most often in highly displaced fractures and those of the outer third. Pathological fracture may result from radionecrosis (following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma) and may be mistaken for a local recurrence.

6 Diagnosis: Clinically there is tenderness at the fracture site; sometimes there is obvious deformity with local swelling, and the patient may support the injured limb with the other hand. In cases seen some days after injury, local bruising is often a striking feature. Diagnosis is confirmed by appropriate radiographs; a single AP projection of the shoulder is usually adequate in the adult.

7 Treatment (a): The most important aspect of treatment is to provide support for the weight of the arm in which the clavicular tie has been impaired. As a rule this is best achieved with a broad arm sling (1). Additional fixation may be obtained by wearing the sling under the clothes (2). No other treatment is needed in greenstick or undisplaced fractures.

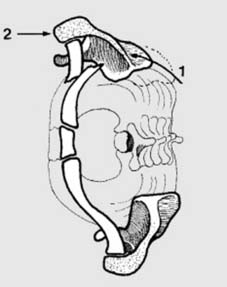

8 Treatment (b): Where there is marked displacement of a clavicular fracture an attempt to correct the anterior drift of the scapula round the chest wall (1) and improve the clavicular shortening is sometimes made. There is no simple way of achieving this. All methods attempt to apply pressure on the front of the shoulder (2) and although they are comparatively ineffective in terms of reduction, are helpful in reducing pain.

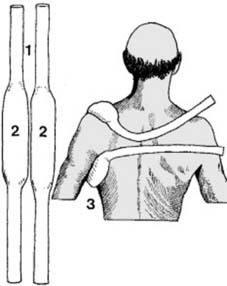

9 Treatment (c):Ring or Quoit method: Narrow gauge stockingette is cut into two lengths of about a metre each (1). The central portions are stuffed with cotton wool (2). One of the strips is taken and the padded area positioned over the front of the shoulder and tied firmly behind (3).

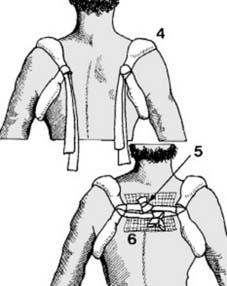

10 Treatment (d): The second strip is applied in a similar manner to the other shoulder (4). The patient is then advised to brace the shoulders back and the free ends of the ring pads are tied together (5). A pad of gamgee (a sandwich of cotton wool between layers of gauze) may be placed as a cushion beneath the knots (6).

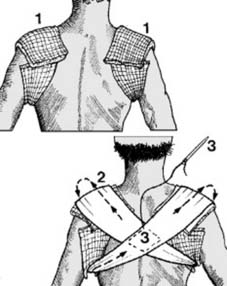

11 Treatment (e): Figure-of-eight bandage: Pads of gamgee or cotton wool alone are carefully positioned round both shoulders (1). The patient, who should be sitting on a stool, is asked to brace back the shoulders; a wool roll bandage is then applied in a figure-of-eight fashion (2). For added security the layers may be lightly stitched together at the crossover (3).

12 Treatment (f): Commercially available clavicle rings, covered with chamois leather, may be applied and secured with a strap. Many other patterns of off-the-shelf clavicular supports are available. With all of these care must be taken to avoid pressure on the axillary structures and the additional support of a sling is desirable for the first 2 weeks or so. Note also that elderly patients tolerate clavicular bracing methods poorly, and sling support only may be advisable. (For internal fixation see Frame 25.)

Note: If there is evidence of torticollis accompanying a clavicular fracture, further investigation of the cervical spine is indicated, as this finding may indicate a coincidental injury at the C1–2 level (locked facet joints). If plain radiographs are insufficient to clarify the situation, a CT scan should if possible be carried out.